2.3 Paris : The City

Noise

Paris was well-known for its noise and bustle. A huge amount of people lived and worked in the city creating crowds everywhere. One of the frames of reference for artists travelling to Paris are images, that give an idea of the continuous assault on the senses as for instance a painting of one of the many bridges across the Seine in which a buildup of traffic plays an important part [1]. One can almost hear the frustrated shouts from the drivers and the sound of hooves and wheels ring out over the river. The artist chose his position carefully, maybe even consciously, away from the crowds preferring the banks of the Seine to the din on the bridge.

1

Antonie Waldorp

Paris, view of a bridge over the river Seine, 1833 (dated)

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. A3849

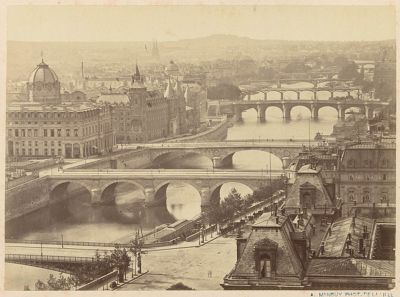

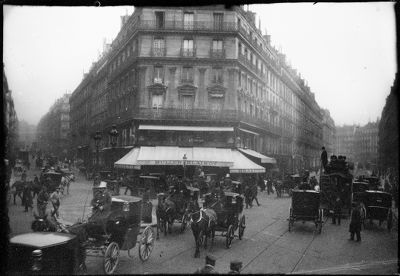

Photographs may create a more immediate response with the viewer, although the first photographs often give a sanitized version of the noise and the crowds, due to the lighting exposure of many minutes [2]. As photographic techniques improved, it became possible to capture short moments in time, giving a better idea of the amount of movement and accompanying noise that went on in a large city such as Paris [3].

Images may evoke the feeling of a city and its impact on newcomers but contemporary publications and writings complement the picture significantly. As early as 1830 the author Amédée de Tissot wrote about the noise of traffic: ‘l’insupportable bruit que font nuit et jour vingt mille voitures particulières dans les rues de Paris’.1 Twenty thousand privately owned carriages in 1830 and the amount was growing fast. By the end of the nineteenth century traffic had grown to such proportions that Charles Baudelaire described carriages as ‘death coming at a gallop’.2

Indeed, when one reads the letters nineteenth-century Dutch artists wrote to their family and friends who stayed behind, be it around 1800, 1850 or 1914, they all carry the same impression of Paris. They were overwhelmed by the crowds – a city boiling with humanity. At the same time they found the traffic incredibly busy and noisy. Jac van Looy called Paris a large monster, being equally impressed by the houses and the machine-like racket of the vehicles in the streets.3

2

Anonymous France 1860-1870

View of the Seine, Paris, 1860-1870

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-F-F16430

3

George Hendrik Breitner

Paardenkoetsen te Parijs, c. 1900

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 343

Filth

A second striking aspect of the city, as stated by the Dutch visitors, was the dirt. Hygiene according to the painter Frederik Hendrik Kaemmerer was not one of the virtues of the French. He dreaded visiting certain areas of the city because of the filth.4 Not only the state of the streets was object of remark but the cleanliness of the hotels and the rooms that were for rent also left somewhat to be desired, if we believe the commentary. When artists comment on the filth, the association with the smell of the city is quickly made.

Publications on Paris underscore the Dutch artists’ viewpoint. The author – Louis-Sébastien Mercier – described Paris as being ‘an amphitheater of latrines piled on top of each other, toilets adjoining stairs, standing next to doors, near kitchens and all of them spreading an incredible stink. The center of science, art, fashion and good taste was also the center of horrific smells’.5

Paris was indeed notorious for its noxious odors and its filth in the streets long before the nineteenth century. Foul smells signaled a crisis in the late 18thcentury when the walls of a mass burial pit gave way. The Cimétière des Innocents was literally leaking into the homes of near residents. By the nineteenth century overcrowding had led to hygienic alarm. It was the offal of everyday life, the daunting volume of all organic matter produced, consumed and excreted by nearly a million Parisians, as well as the slaughterhouses and waste dump in the quartier Montfaucon in Northeastern Paris and backed up and leaking sewers, in combination with a changed attitude to odours and bodily hygiene, that engendered the realization that action had to be taken.6 From the beginning of the nineteenth century improvements and changes were made, slowly turning the French capital into a modern and clean city. Baron Haussmann’s works and the enlargement of the sewage system in the fifties and sixties gave an enormous boost to the clean-up of the city, but it would take until the first half of the twentieth century before Paris was a relatively odourless city. Until then, Dutch visitors often found themselves complaining about the situation.

Beauty

Some artists may have had reservations, but most were enamored by what they saw: Paris was colourful and picturesque filled with exotic and interesting people, buildings and sights. Kaemmerer was fascinated: ‘beautiful, grand, even picturesque, with fountains and colossal monuments, fascinating costumes worn by zouaves and dragoons wearing red coats creating a colourful effect. Besides the soldiers there is a variety of other clothing. One sees the strangest types: from the rich in their carriages to the rag-picker who rummages through the filth in the streets with his hook, the market women and the street worker who looks like a wild animal in his cloak made of cow skins’ [4].7 The buildings were regarded with equal admiration: the writer Jan Hofker recalled the construction of the new Gare d’Orléans on the quai d’Orsay calling the building a fairytale castle. However, not everybody was enthusiastic: the houses, which often had seven stories, were intimidatingly high, blocking out most of the light in the streets and giving quite a few artists the feeling of being buried alive.

Of course most Dutch artists and visitors came to Paris to see the art that could be found in the Louvre, in Musée Cluny and in the Musée du Luxembourg, at the Salons and in the windows of the art dealers. Most reactions were lyrical: Dutch artists were generally of the opinion that artworks of such excellent quality could only be found in the French capital. Obviously the choice of works that were singled out for praise differed, depending on when artists were in Paris. August Allebé – who stayed in Paris between 1858 and 1860 – was fascinated by the collection of the Louvre and made copies after, among others, Bartholomé Esteban Murillo and Jean-Baptiste Chardin. At the same time he was impressed by both Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Eugène Delacroix and met artists such as Gustave Courbet and Henri Fantin-Latour. Thirty years later it was Jules Bastien-Lepage and Jean François Millet who fascinated the Dutch visiting painters.

Interesting, however, was the continuous interest, throughout the century, in the Dutch seventeenth-century works of art that could be found in French collections. Almost all nineteenth-century Dutch visitors commented on the Dutch Old Masters that they viewed in Paris, be it in museums or in private collections. It would seem that this interest was shared by French- and Dutchmen.

4

Frederik Hendrik Kaemmerer

Waving crowd at an ascending balloon

Notes

1 A. de Tissot, Paris et Londres comparés, Paris 1830, p. 172.

2 ‘Mon cher, vous connaissez ma terreur des chevaux et des voitures. Tout à l'heure, comme je traversais le boulevard, en grande hâte, et que je sautillais dans la boue, à travers ce chaos mouvant où la mort arrive au galop de tous les côtés à la fois, mon auréole, dans un mouvement brusque, a glissé de ma tête dans la fange du macadam’, C. Baudelaire, ‘Perte d’Auréole’, in: Petits poèmes en prose (Le Spleen de Paris), Paris 1869, no. 46.

3 Letter Jacques van Looy to August Allebé, 18 January 1887, F.P. Huygens, ‘Wie dronk toen water!’ Bloemlezing uit de briefwisseling met August Allebé gedurende zijn Prix de Rome-reis 1885-1887, Amsterdam 1975, p. 289.

4 Letter Frederik Hendrik Kaemmerer to Johan Philip Kaemmerer, 7 April 1865, J. Versteegh (ed.), F.H. Kaemmerer 1839-1902, Oosterbeek 2001.

5 L.-S. Mercier, Tableau de Paris, Hamburg/Neuchatel 1781, in: A. Corbin (translation K. van Dorsselaer et al.), Pestdamp en bloesemgeur. Een geschiedenis van de reuk, Nijmegen 1986, p. 46.

6 Corbin 1986 (note 10), p. 46.

7 Letter Frederik Hendrik Kaemmerer to Johan Philip Kaemmerer, 7 April 1865, Versteegh 2001 (note 9).