6.1 An Image of the Country

During the nineteenth century, travel conditions improved throughout Europe. The rapidly expanding rail network made Spain more easily accessible from countries in northern Europe. Yet despite these infrastructural improvements, Spain still had a fairly unspoilt landscape. The combination was ideal for artists. Northern Europeans may well have been drawn by the idea that they did not have to go to Africa or even further to discover a landscape and culture profoundly different from their own. The influence of Moorish rule – which had lasted almost 800 years, until 1492 – was still clearly visible in Spanish architecture, especially in the south. Southern Spain was also home to gypsies (Roma), an ethnic group with a non-Western character. Accordingly, the most popular Spanish destinations other than Madrid were Granada, Seville and Córdoba.

Artists’ travels in Spain and the works of art that they produced there can be understood in the context of Orientalism. Because little was known about most ‘Oriental’ countries, many artists sought to record the daily lives of the people there in an almost documentary fashion. In practice, however, they typically portrayed not just everyday life, but also scenes with an exotic ambiance set in Turkish baths or at popular festivals and invariably flooded with brilliant sunlight. For example, Gustav Bauernfeind’s painting of a market in Jaffa (now in Israel) combines characteristic architecture with colourful garments and sharp-edged shadows cast by the blazing sun.

The Hispanists, as the travellers to Spain were sometimes called, had an artistic preference for exotic, characteristically Spanish subjects, such as dancing, gypsies and bullfighting. The urge to portray ‘otherness’ was certainly among their motives for going to Spain. Since these artists – especially the French and German ones – tended to depict these novel subjects in a sun-drenched setting, their paintings, like those of the Orientalists, have deep shadows and intense colours. This type of exotic atmosphere is found less frequently in the work of Dutch Hispanists.

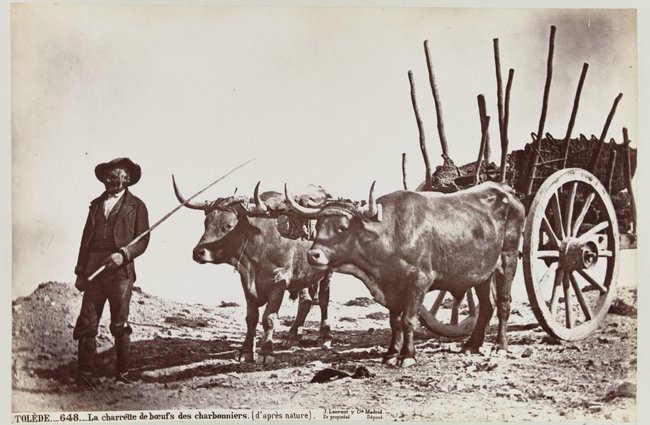

The popular stereotype of Spain in Northern Europe was influenced by travel guides,1 plays such as Bizet’s opera Carmen, literary works like Cervantes’s Don Quixote, magazine articles and travel photography. The same images recurred in many photographs of Spain, creating a skewed, simplistic image of the country. One good example of these clichéd images is a photograph of a man with an oxcart, part of a series of photographs sold under the title of Spanien und Marokko. The well-known French travel photographer Jean Laurent (1816–c. 1896) took this photo between 1857 and 1880. It is revealing to compare it to a drawing reproduced in Jozef Israëls’s Spanje, een reisverhaal (1899) [1].

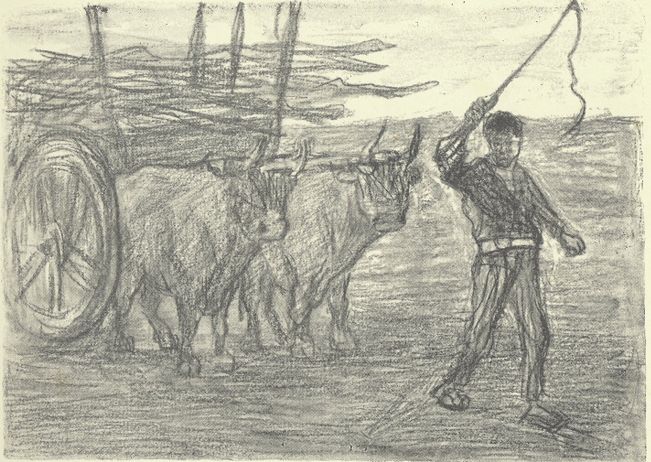

Israëls’s drawing likewise depicts a man with an ox-drawn cart [2]. The pose and direction of movement of the man with the whip differ, but the resemblance is unmistakable. This is not to imply that Israëls used the earlier photo as a model, or even saw it. The similarity between the two images does, however, illustrate how certain clichés influenced perceptions of Spain.

In search of Spanish art

During the nineteenth century, classical painting began to lose its pre-eminence, and resistance to the rules of academic art started to grow. There was a new, deep-seated desire for realistic art, which portrayed people as they really were. The works of the Spanish masters – naturalistic figure pieces in dark colours – served as a useful model for painters with realist tendencies. For instance, in the painting Carlos de Austria, infante de España by Diego Velázquez, the matt, empty background focuses all the attention on the young man [3]. His clothes, especially his gloves and hat, look very authentic, and they are rendered in brushstrokes that are strikingly loose for their day. It was these stylistic traits that later won Velázquez the title of the father of modern art.

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, around twenty Dutch artists travelled to Spain.2 The Dutch discovery of Spain came fairly late. British artists were the first to visit the country, and the Germans, Americans, and Belgians also preceded the Dutch, but it was the travels of French artists that are most relevant here. Eugène Delacroix went to Spain in 1832, and Edouard Manet and Gustave Courbet followed in the 1860s. Of these three artists, Manet may be the best known as a Hispanist, because of the many Spanish subjects in his work, such as bullfighters and women in Spanish costume, and because his style of painting was inspired by Velázquez [4].

Around 1885, this French artist became the object of considerable fascination in the Netherlands, a trend sometimes referred to as Manetism. Many reproductions of his work were in circulation, and his Dutch admirers must have noticed his fondness for Spain. In any event, Dutch artists could have been exposed to Spanish art and culture in Paris; Van Looy and Israëls both visited Paris before travelling to Spain.

1

Jean Laurent, Toledo. The coal miners’ ox-cart (from life), c. 1857-1880

albumen print, 225 x 337 mm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

2

Jozef Israëls

Boy with an ox cart, 1899

Whereabouts unknown

3

Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez

Portrait of Carlos de Austria, infancte de España (1607-1632), 1626-1627

Madrid (city, Spain), Museo Nacional del Prado

4

Édouard Manet

Mademoiselle V in the costume of an espada, 1862

New York City, The Metropolitan Museum of Art