7.2 The Pioneering Role of John Forbes White

Art had gained significant importance during the British Victorian period. The middle class was expanding, and with its new wealth and power, the class also pursued membership of the gentry in order to gain status and social distinction. According to Pierre Bourdieu, what differentiated the members of the middle class and those of the aristocracy was the scholastic upbringing of the former, opposed to the supposed ‘natural’ relationship that the gentry had with culture.1 The aristocracy had important art collections by means of purchase and inheritance, and thus, the new bourgeoisie also started creating art collections to achieve social distinction. These ‘new aristocrats’ had to buy paintings, however, because their families did not own art collections to pass down to their children, and focused on contemporary art, which was easier to obtain and could be commissioned to the customer's personal taste (i.e. subject matter, style, handling, etc). The key role of art collecting in the quest for achieving higher social status is the reason why mid-nineteenth-century art collectors took their work very seriously.

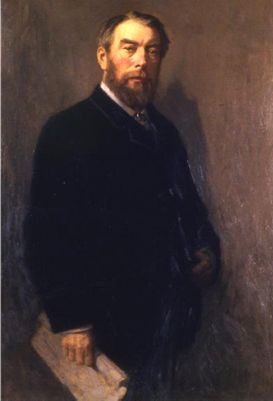

John Forbes White provided the Scottish middle class with art that would satisfy their tastes and needs. White was a leader and innovator in the flour milling industry, a politician, a university administrator, a scholar, a photographer and he was passionate about art [3].

In 1862, White visited the World Exhibition in London where works by the Dutch painters Jozef Israëls and Alexander Mollinger from The Hague School were on display. The impact of these paintings on White led him in 1866 to arrange for the young Scottish painter George Reid to study under Mollinger in the Netherlands. As a result, the young Reid stopped producing Scottish Romantic landscape paintings à la McCulloch and adopted The Hague School’s painting style. Two years later, White and Reid published a pamphlet entitled Thoughts on Art and Notes on the Exhibition of the RSA of 1868 signed ‘Veri vindex’ (Truth Will Conquer), in which they argued that a revival of the fine arts in Scotland was only possible by moving in a new artistic direction.

3

George Reid

Portrait of the collector John Forbes White, 1889 dated

Aberdeen (city, Scotland), Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums

Veri Vindex considered the art scene in Scotland to be waning and strongly advised artists and the Royal Scottish Academicians to study and be inspired by what was being made in other countries. Unlike history painting, with its historical inaccuracies and difficult to decipher subject matter, the pamphlet praised landscape and genre paintings for its display of life, vigor and sentiment in a contemporary fashion. It is French art, according to the authors, that deserved the highest admiration: ‘In no country is the poetry of the simple peasant life more keenly felt […] (and treated) with exquisite pathos and feeling’. One key aesthetic element of this school was the technique of the tonalité. ‘The tonalité of a picture [...] means the gamut of tonic values...’ that must pervade the whole picture. Veri Vindex pointed to contemporary French landscape and rural artworks, which were painted using the tonal technique, as the style to follow. The Hague School paintings were also celebrated for using this technique shared with contemporary French art. After Mollinger’s death in 1867, White was able to purchase all the remaining works of the Dutch artist, which he took back to Scotland in order to sell to his friends.2 No longer just an art critic, White had also become an art dealer.

The Art Dealer as a Shaper of Artistic Taste

The first Scottish collectors of The Hague School paintings were those all associated with White. Some of The Hague School paintings imported by White were displayed to the public at the RSA exhibitions in Aberdeen. According to Laura Newton, White organized an exhibition at Aberdeen’s town hall in 1873 and displayed works by Israëls, Mollinger, Gerard Bilders, Johannes Bosboom, David Adolph Constant Artz and Willem Roelofs (all the paintings coming from private collections); ‘...it was probably the success of this exhibition which persuaded Craibe Angus to go into partnership with Daniel Cottier to bring Hague School pictures to Glasgow in 1874’.3 This explains why the great bulk of Hague School paintings went to Glasgow's private collection, instead of Aberdeen where the first paintings by this Dutch school went.

Cottier, who owned the art gallery Cottier & Co in London, began selling works from The Hague School after the aforementioned partnership. He also opened a branch in Glasgow that was managed by William Craibe Angus. Interestingly, Dieuwertje Dekkers explains that in the late 1870s a great number of paintings by early-nineteenth-century Dutch artists that Cottier originally sent to his American branch were brought to Glasgow. These were cheaper, easy to market paintings by Petrus Paulus Schiedges, Petrus Gerardus Vertin and Anthonie Jacobus van Van Wijngaerdt among others, which the art dealer used to introduce Dutch art to the art buying public. Having done this, the art dealer slowly molded the taste of the customer by progressively offering the more expensive artworks of The Hague School.4

This marketing strategy proved to be extremely successful. A large international network of art dealers flourished during the 1880s with galleries and branches in Paris, The Hague, London and Glasgow selling Dutch works. Some of the most renowned art dealers were Goupil & Cie., Buffa & Co., David Croal Thomson, Ernest Gambart and Henry Wallis. They expanded the art business by commissioning paintings by artists and even ‘buying the artists’ exclusivity of production’, and by acting as intermediaries between a fellow art dealer and the customer or the artist. By the end of the century, other art dealers also began selling The Hague School art in Glasgow, such as Thomas Lawrie, William B. Paterson and Alexander Reid.

Notes

1 P. Bourdieu, Distinction. A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, London 1996, pp. 68-71.

2 J. Melville, ‘Capturing the Impression of the Moment. John Forbes White and the Road to Impressionism in Scotland’, in: F. Fowle, Impressionism and Scotland, Edinburgh 2008, p. 22.

3 3. Newton, ʻCottars and Cabbages. Issues of National Identity in Scottish “Kailyard” Paintings of the Late-Nineteenth Centuryʼ, Visual Culture in Britain 6 (2005) no. 2, p. 54.

4 For more information on this and on several other art dealers’ marketing strategies see D. Dekkers, ‘Goupil en de internationale verspreiding van Nederlandse eigentijdse kunst’, Jong Holland 11 (1995), no. 4, p. 32.