7.3 The Scottish Art Collector’s Needs Solved

The popularity of art of The Hague School in Scotland was a phenomenon that was driven by the Scottish collectors’ needs. A close look at the works reveals two key factors: The Hague School paintings tried to evoke the work of seventeenth-century Dutch painters by depicting flat landscapes and low horizon-lines with cows, windmills, peasants and fishing folk [4-5].

The resemblance of these paintings with those of the Dutch Golden Age was a conscious decision by artists in order for their work to gain legitimacy. These works were popular among the modern bourgeoisie who sought art rooted in the style of the Old Masters, which were favored by the aristocracy. The aristocracy, the landed gentry with extensive tracks of land, had traditionally been the consumers of landscape painting. Thus, in order to the gain status, industrialists and other new bourgeoisie groups preferred this type of painting in the second half of the nineteenth century. An important aspect of the bourgeoisie’s passion for the painted landscape was the illusion the paintings provided of rural life undisturbed by modernity (i.e. railways, factories, etc).

Rural life was idealized and celebrated by the bourgeoisie, creating what Robert L. Herbert calls the myth of primitivism.1 This myth valued simplicity, virtuous work, and innocence, which were considered to be defining elements of rural life. The people of the rural working class were also viewed as tragic characters because of the demanding physical labor they had to perform, which often led to injury or death [6].

4

Willem Maris

Meadow with cows near a pond, 1880-1904

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. SK-A-2428

5

Jacob Maris

Village in the neighbourhood of Schiedam

Dordrecht, Dordrechts Museum

6

Jozef Israëls

Fishermen carrying a Drowned Man, 1861 probably

London (England), National Gallery (London), inv./cat.nr. NG2732

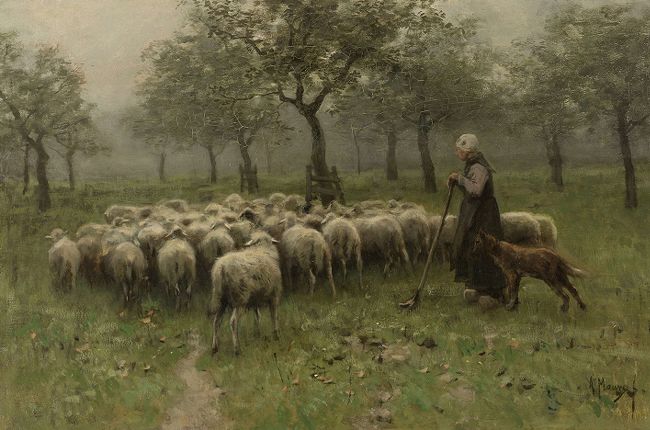

7

Anton Mauve

Shepherdess with a flock of sheep, 1870-1888

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. SK-A-3184

Wendy Joy Darby argues that ‘The development of sentiment was what it was all about, yet engagement with what was seen, the human misery, was not’.2 Rather than confronting the reality of rural misery, the paintings allowed the bourgeoisie to believe and spread the idea that the rural folk was content with their lives [7]. On the canvas, peasants and fishermen look like they accept their position in life and do not blame the urban bourgeoisie for their low standard of living. Grayish and pinkish tones help to reinforce the idealized view of rural life and uphold bourgeois instead of a revolutionary representation of the rural working class.

The Hague School paintings, however, had several transgressive elements that were modern for its time. They presented contemporary rural life in a descriptive manner, showing animal or human activity [8]. The paintings, with their simple subject matter, followed the Victorian ideal that anyone should be able to understand the art by simplifying its elitist language. The aforementioned technique of the tonalité made the paintings look aesthetically similar to contemporary French painting, and therefore, had a cosmopolitan quality [9]. Furthermore, the loose brush strokes used to create the paintings differed from the traditionally precise style of the Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic Movement found in England [10], and highlight the modern artistic taste found in Scotland. The Hague School technique was considered innovative and aesthetically challenging at the time, implying that the art collector who acquired works from this school had modern artistic taste.

8

Hendrik Willem Mesdag

Pinken in de branding

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. A 2670

9

Anton Mauve

Horsemen in the snow, 1880

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. SK-A-2443

10

Jan Hendrik Weissenbruch

The canal near Noorden

Dordrecht, Dordrechts Museum